Avian Botulism

Shawn Swearingen for SPLIT REED

Photos Courtesy of Bird Ally X

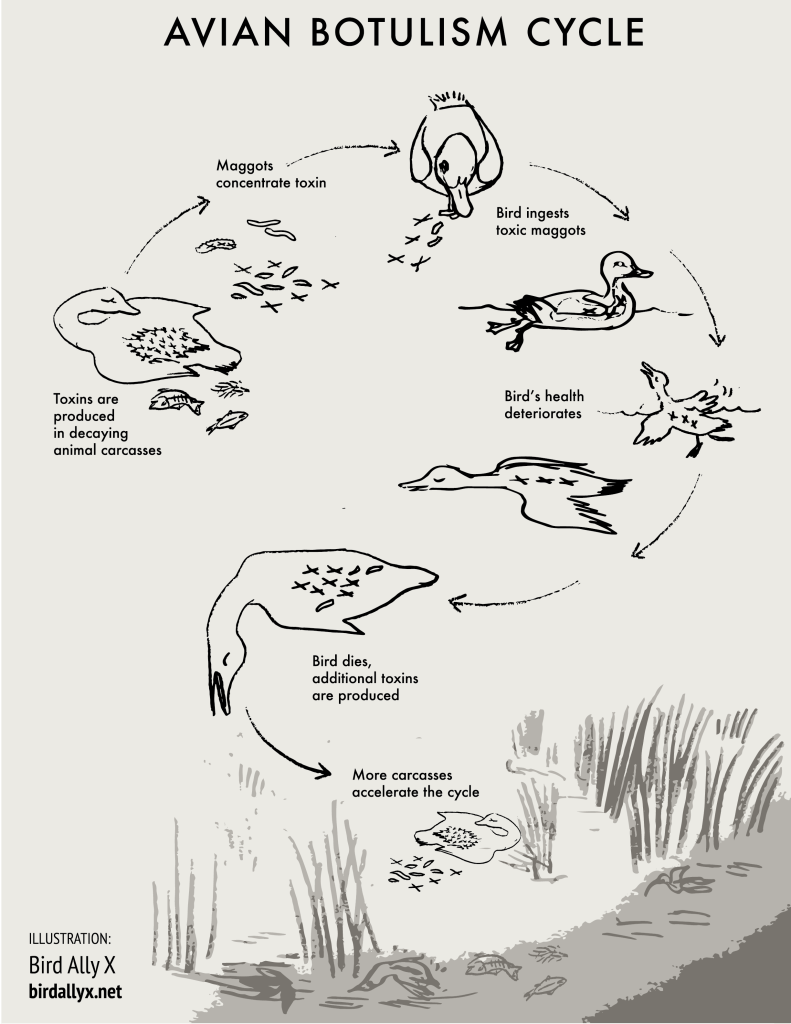

Knowing a little about the science behind the cause of the illness affecting waterfowl will help understand the broader picture of the status, so we’ll start with a ‘Cliff Notes’ version of biology. Avian botulism is a naturally occurring bacteria that is in the soil and when it comes to life, produces a toxin. Waterfowl can get it by eating aquatic invertebrates which filter feed on sediments in the water. The toxin attacks the nervous system of the bird, inhibiting muscle movement, leading to the clinical signs: weakness, lethargy, and inability to fly or hold the head up. This is what leads to the deaths of the birds, drowning. After a few ducks succumb to this, maggots appear. The maggots amplify the lethality of the toxin and the outbreak explodes as other birds eat these time-bomb maggots. Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge alone lost an estimated 50,000 ducks to avian botulism in 2020.

Brian Huber, a waterfowl biologist for the California Waterfowl Association (CWA), says that the usual timing of botulism hits hard when birds are molting. “Birds that are molting need protein. This is when they are eating a heavy diet of aquatic invertebrates that are holding the toxins.” When the birds die and are not picked up by biologists during surveys or banding programs while they are in the marsh, biomagnification occurs when other birds eat the maggots off of the expired birds that hold the toxins. In the areas of Klamath and Tule Lake National Refuges, Bird Ally X was established by volunteers to nurse back those birds that are found with clinical signs of avian botulism. Flushing out the system with a fresh diet and water, and then released, has helped reduce the numbers lost. Usually, the rehabilitated birds are banded to follow up on how well they do after rehabilitation.

On the bright side of 2021, there does not seem to have been widespread outbreaks of avian botulism that have been witnessed in previous years. Both Dr. Chris Nicolai of Delta Waterfowl and Brian Huber remarked that regional biologists were prepared for outbreaks in their areas but several factors occurred to limit this potential. What water there was even in drought-stricken Klamath Falls, Tule Lake, and Stillwater refuge systems, enough fresh water and movement happened thanks to rain or pumping in of water [more on that soon] that limited the likelihood. Cooler overnight temperatures also aided in keeping water temperatures and outbreaks down.

One question that lingers is when you look at the overall numbers, avian botulism does not account for a high percentage of waterfowl loss. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) estimated in a 2016 release, that 20% of birds shot and downed by hunters are not recovered; a number that can range in the millions. So, why does avian botulism seem to be talked about so much more than say taking better shots and retrieving game? My current hypothesis is this, it isn’t the result of avian botulism, it is the underlying symptom that alarms us: poor habitat conditions.

Poor wetland habitat and management areas can lead to much more than avian botulism. It can increase the predation of young birds and the molting, poor or inadequate nesting habitat, as well as an increase in invasive species including both flora and fauna. There are man-made options to assist in creating and maintaining habitat yet there are some things like snowpack or rainfall that only Mother Nature can control. CWA and its donors have stepped up in Tule Lake National Refuge for example by securing water rights from landowners this year. By doing so, they are able to pump fresh water into the system which helps keep the botulism concerns and water temperatures low. This also aids in having the necessary water available to molting birds and those migrating birds that are starting to arrive.

Helping groups like CWA and volunteering time can certainly improve the needed wetlands in the long run. While USFWS cites several ways to combat avian botulism, the common denominator is better water and wetland management.

For more Split Reed Original Content click here.